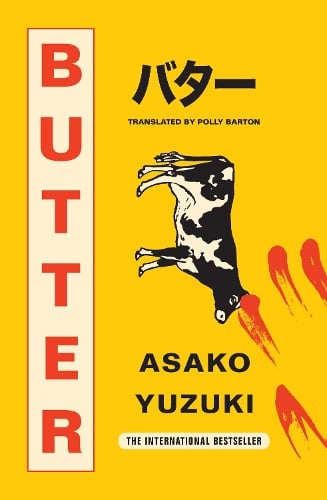

Asako Yuzuki’s novel, Butter, has captivated readers with its unsettling premise and achieved remarkable accolades, including the Waterstones Book of the Year 2024. Yet, to see Butter merely as a sensational, food-centric crime novel would be to miss the rich, complex, and often provocative tapestry Yuzuki weaves. It’s an invitation into a world where culinary arts meet sharp social critique and the quest for a story becomes a profound journey of self-discovery.

Born in Tokyo in 1981, Asako Yuzuki is a distinctive voice in contemporary Japanese fiction. Her path to becoming a novelist was paved with diverse experiences. An alumna of Rikkyo University with a degree in French literature, her senior thesis delved into the intricate social realism of Honoré de Balzac – an early indication, perhaps, of her keen observational eye for societal structures. A brief stint at a confectionery maker also hints at the gastronomic fascination that would later permeate her work. However, a pivotal moment occurred during a serious illness in junior high school, when she encountered Banana Yoshimoto’s Kitchen. This experience, she has shared, redirected her towards Japanese authors. Her themes of vulnerability, solace, and the profound comforts found in domesticity and food echo powerfully in her narratives.

Yuzuki made her literary debut in 2010 with ‘Shuuten no ano ko’. This collection included ‘Forget Me, Not Blue,’ a story that won her the All Yomimono Prize for New Writers. This was just the beginning of a career that would see her nominated multiple times for the prestigious Naoki Prize and win the Yamamoto Shūgorō Prize for Nairu pāchi no joshikai (Nile Perch Women’s Club).

The Main Course: Deconstructing ‘Butter’

Butter, Yuzuki’s first novel to be translated into English, is where many international readers first encounter her potent blend of storytelling. The novel draws its chilling inspiration from a real-life Japanese crime: the case of Kanae Kijima, dubbed the ‘Konkatsu Killer,’ a woman convicted of seducing and murdering several men she met through matchmaking websites, often using her culinary prowess as a lure. But Yuzuki doesn’t simply rehash sensational headlines. Her intent was more profound: to push back against the predominantly male-centric media coverage of Kijima and to critique a society where men often seek stereotypical ‘dream women’ as wives.

The narrative unfurls through the eyes of Rika Machida, a journalist in her early thirties, hungry for a career-defining story. She secures interviews with Manako Kajii, the enigmatic gourmand and convicted serial killer awaiting retrial. Kajii, whose physical appearance defies conventional Japanese beauty standards, is infamous for allegedly using her exquisite cooking to ensnare wealthy men before their demise.

Initially driven by ambition, Rika is drawn into Kajii’s powerful orbit. Their prison interviews morph into what one reviewer aptly termed a masterclass in food. This unexpected gastronomic mentorship ignites a profound transformation in Rika. She begins to cook, to truly taste, and, significantly, to gain weight, forcing her to confront Japan’s exacting beauty standards and the deeply ingrained patriarchal views on women’s bodies and roles. Rika’s journey is one of challenging ‘feminine thinness,’ a path towards self-acceptance and autonomy that is both exhilarating and fraught with societal judgment.

Manako Kajii, the catalyst for Rika’s awakening, is a figure of fascinating contradictions. She is a passionate, almost hedonistic cook, yet espouses seemingly traditional views, declaring, ‘There are two things that I can simply not tolerate: feminists and margarine’. For Kajii, butter symbolises ‘unapologetic indulgence and the ideal of being a stay-at-home wife,’ while margarine epitomises the ‘fake’. Through Kajii, Yuzuki seems to question rigid ideologies, suggesting that true female agency might lie beyond established norms, even some feminist ones.

Thematically, Butter is a lavish spread. Food is central – a language of indulgence, pleasure, desire, control, and self-acceptance. Yuzuki’s prose is rich with sumptuous descriptions that make the reader almost taste and smell Kajii’s creations. But beneath this sensory layer lies a vivid, unsettling exploration of misogyny in Japan. The novel dissects patriarchal views, the immense pressure on women to conform, to be ‘palatable pieces to be consumed by the culture’, and the ‘Konkatsu’ (marriage-hunting) culture itself. It’s a nuanced exploration of feminism, not as a monolith, but as a spectrum of experiences and interpretations.

Interestingly, the reception of Butter has been markedly different at home versus abroad. Internationally, it’s been hailed as a cult classic. Yuzuki herself expressed surprise, having initially thought the unchecked misogyny portrayed in Butter was a specifically Japanese problem. In Japan, however, the response was more muted, with some critics labelling it too harsh, feminist, and indulgent. This divergence perhaps underscores the novel’s role as a cultural barometer, highlighting both the universality of its themes and varying societal readiness to confront them.

Beyond ‘Butter’: A Taste of Yuzuki’s Wider Literary World

While Butter is a formidable introduction, Asako Yuzuki’s literary repertoire extends further. She consistently explores women’s intricate lives against the backdrop of contemporary Japan. Her debut, Shuuten no ano ko (2010), which included the award-winning ‘Forget Me, Not Blue,’ tackled bullying in an all-girls school, immediately signalling her interest in the complex, often challenging, dynamics of female social worlds.

In Ranchi no Akko-chan (Akko’s Lunches, 2013), Yuzuki offers a warmer portrayal of female connection through four linked stories about a young office worker and her older boss, their evolving mentorship often facilitated by shared meals. Japanese readers have frequently described it as an uplifting ‘vitamin novel,’ offering encouragement and a fresh perspective on daily life.

Conversely, the award-winning Nairu pāchi no joshikai (Nile Perch Women’s Club, 2015) delves into far darker territory. It’s a twisted tale of a friendship between a career woman and a popular housewife blogger that spirals into obsession, psychological manipulation, and blackmail. Japanese reviews laud its excellent psychological depiction and the intense pressure of female relationships, with one critic noting how an expected heartwarming ending gives way to a rampage of obsession.

Other notable works include Itō-kun A to E (2013), which dissects unhealthy relationships and male narcissism through the eyes of several women interested in the same man, and Honya-san no Daiana (Diana the Book Clerk, 2014), a celebration of female friendship and the solace found in literature.

The Signature Ingredients: Yuzuki’s Recurring Motifs and Distinctive Style

Across her diverse narratives, certain ingredients consistently flavour Asako Yuzuki’s work. Food, as we’ve seen, is paramount. It’s a conduit for pleasure, a tool of power, a symbol of self-care, and a medium for social commentary. Her brief experience in a confectionery company lends an extra layer of authenticity to her often luscious descriptions.

Another constant is a critical examination of gender dynamics and female agency. Yuzuki consistently challenges restrictive norms and explores the multifaceted nature of feminism, a consciousness she admits has evolved, particularly through her experiences with childcare and the pandemic. This is often intertwined with a sharp critique of societal beauty standards and the intense pressure on women’s bodies.

The complexities of female relationships form a rich thematic vein. She masterfully portrays the entire spectrum, from the supportive bonds in Ranchi no Akko-chan and Honya-san no Daiana to the toxic obsession in Nairu pāchi no joshikai. Yuzuki has noted how the interpretation of her depiction of these relationships has shifted over time, from being seen as ‘doro-doro’ (messy or mucky) to being recognised for portraying ‘sisterhood’ and ’empowerment,’ a change that may reflect broader cultural shifts in Japan.

Her narrative style is often praised for its descriptive, vivid language, especially when evoking food. Her novels are character-driven, offering deep dives into the inner lives of women who are ‘dynamic… not easily categorised’. Many find her storytelling atmospheric, a slow burn that allows for heightened sensory experience and immersion, though this deliberate pacing can sometimes be perceived as lengthy by others.

The Author at Her Desk: Craft and Method

Yuzuki’s literary craft is informed by a blend of influences and a distinctive working method. Her early reading included Western authors like Beverly Cleary and Judy Blume, followed by the pivotal encounter with Banana Yoshimoto, and later, an academic grounding in Balzac. This fusion of Western YA’s focus on female interiority, Yoshimoto’s introspective Japanese sensibility, and Balzac’s social realism seems to have forged her unique voice.

Her writing process involves meticulous research; for Butter, she took French cooking classes for a year. She employs a ‘scrapbook technique’ of collecting inspiring material, which she also uses to ‘reverse think’ her themes by identifying what doesn’t interest her, helping her sharpen her focus on her passions. She also collects everyday observations—moments of joy, sorrow, or humour—and then builds narratives around these emotional cores. She believes persistence is paramount, advising writers to continue writing and to view criticism as fertiliser for future growth.

Why Asako Yuzuki’s Stories Savour So Well

Asako Yuzuki’s work resonates because it achieves a delicate balance: her stories are deeply rooted in the specifics of Japanese culture, yet they touch upon universal anxieties and desires. Butter, for instance, while dissecting ‘Konkatsu’ culture and Japanese work ethics, speaks to global audiences about misogyny, body image, and the search for authenticity. She doesn’t shy away from the ‘uncomfortable’ or the ‘harsh,’ presenting flawed, complex characters grappling with brutal truths. This commitment to psychological realism, even in darker shades, gives her fiction an unsettling yet compelling power.

Asako Yuzuki offers a veritable feast in a literary landscape hungry for diverse voices and challenging narratives. Her ability to blend the sensory allure of food with incisive social observation and profound psychological depth marks her as a vital contemporary author. As her feminist consciousness continues to evolve, and as she continues to engage with the complexities of modern life, one can only anticipate that her future works will offer even more to savour, to question, and to discuss. She is a writer who reminds us that sometimes, the most unsettling truths are found in the most unexpected and delicious places.