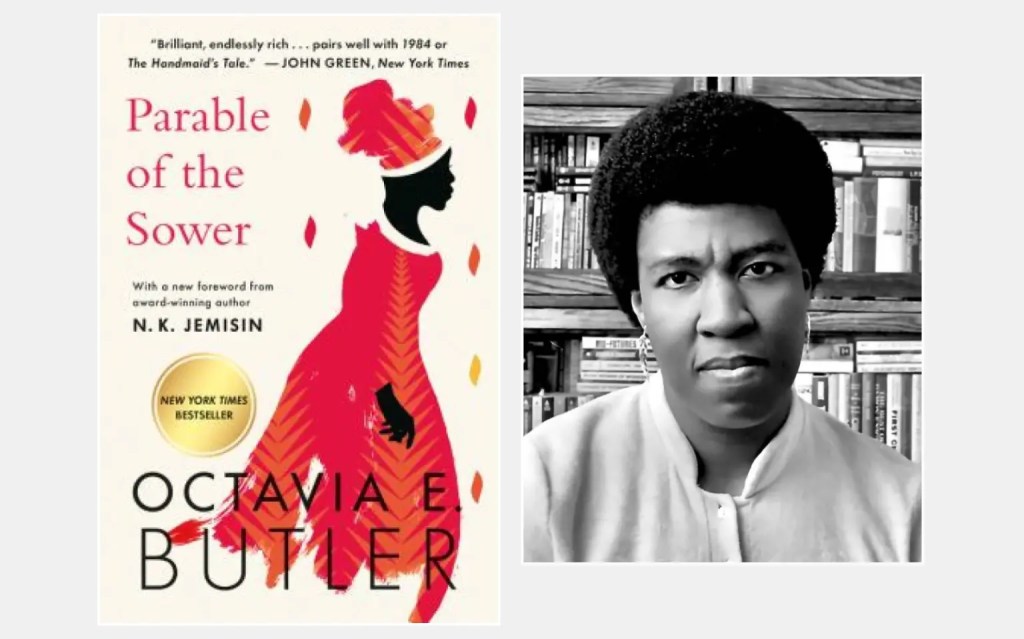

In 1993, a groundbreaking work of speculative fiction offered a terrifying glimpse into a near-future America ravaged by climate change, economic collapse, and social unrest. At the time, Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower was critically acclaimed but remained a powerful, albeit niche, entry in the science fiction canon. Yet, almost three decades later, the novel performed a feat nearly as astonishing as its foresight: it became a surprise best-seller, soaring onto the New York Times list in 2020. This unexpected resurgence was not merely an act of good timing; it was a collective public realisation that the world Butler had so meticulously envisioned was no longer a distant possibility, but a chillingly accurate reflection of our own.

For writers, this story offers a masterclass not only in world-building but in the very purpose of fiction. Butler’s work demonstrates how the most effective speculative narratives are not detached fantasies but logical, extrapolated projections of our present reality. Her novel is a testament to the power of a writer’s unflinching gaze—the ability to look at existing social ills and trace them to their harrowing, yet logical, conclusion. In doing so, she provides a powerful model for how to craft a story that serves not only as a cautionary tale but as a blueprint for resilience. It is a work that asks, and attempts to answer, the most urgent question of our time: once a world begins to fall apart, what does it take to build a new one from its ashes?

The prophetic power of Octavia Butler’s writing is rooted in the stark realities of her own life. Born in Pasadena, California, in 1947, she grew up in a city that, while not legally segregated, maintained de facto racial and social divisions. Her early life was marked by poverty; her father, a shoe shiner, died when she was seven, and she was raised by her mother, a domestic worker, and her grandmother. Butler’s experience of accompanying her mother to wealthy homes and being forced to enter through the “back door” left an indelible mark on her psyche, a direct observation of systemic inequality that would later form the thematic bedrock of her work. She would later attempt to resolve these feelings in her most famous novel, Kindred, but the critique of social stratification is even more explicit in the world of Parable of the Sower.

Butler also had to overcome significant personal challenges to find her voice. She struggled with dyslexia as a child, a condition her teachers often misinterpreted as a lack of effort. Despite this, she was a voracious reader, devouring everything from the literary to the mundane. Her lifelong dream of writing was sparked at the age of nine after she saw a B-movie, Devil Girl from Mars, and thought to herself, “Geez, I can write a better story than that!”.

This moment of creative defiance set her on a path of relentless discipline. She began trying to sell her stories at the age of thirteen, but her early stories were so unconventional that many teachers accused her of having copied them. Her journey to becoming a professional writer was arduous, marked by years of rejection and a series of menial jobs, including telemarketer, potato chip inspector, and dishwasher. Throughout this period, she maintained a punishing schedule, rising at two o’clock in the morning to write before heading to work. This personal history of struggle, persistence, and an unwavering commitment to her craft shaped her literary vision, which always approached the science fiction genre “self-consciously as an African American woman marked by a particular history”.

The political and social critiques embedded in Parable of the Sower are thus deeply personal. The novel’s portrayal of a society divided by literal and figurative walls—where the privileged are insulated within gated communities while the poor and homeless are left to fend for themselves—is a direct echo of her childhood experiences. By transforming her personal experience with segregation and classism into a global social collapse, Butler elevated her work from mere fiction to a searing critique.

Parable of the Sower weaves a complex tapestry of interconnected themes that collectively form a philosophical framework for survival. The novel is less a simple post-apocalyptic narrative and more a thoughtful examination of how societies collapse and how new ones can be built from the ruins. For writers, it provides an example of how to anchor a fictional world with a compelling and consistent philosophy.

The central philosophical tenet of the novel is Lauren Olamina’s new religion, Earthseed, whose core scripture proclaims, “God Is Change”. This belief is a radical departure from the static, traditional Christian faith espoused by her father, which Lauren finds untenable in a world unravelling around them. For Lauren, resisting change is an act of denial that invites a destructive transition. Earthseed posits that change is the only constant and the only lasting truth.

This is not a passive acceptance of fate but an active mandate to engage, shape, and intentionally influence change to achieve transformative results. The novel argues that in a turbulent world, only those who demonstrate “resiliency” and “ongoing individual adaptability” are best able to survive and thrive. This adaptability is manifested through hard work, education, purpose, kindness, and community, which collectively breed a more tangible form of hope than blind faith in a “capricious and, in her mind, uncaring Christian God”. This philosophical framework provides a moral and practical compass for the characters, transforming a story of survival into a chronicle of evolution.

Despite the backdrop of environmental devastation, social decay, and constant violence, the novel is underpinned by a continuous thread of rebirth, regeneration, and rebuilding. Lauren observes life-affirming acts, such as people getting married and having children, even as fires rage across the land. This cyclical view of destruction and creation is central to the Earthseed philosophy. The concept is explicitly symbolised when Lauren raises the notion of a phoenix being reborn from its own ashes before her community is burned to the ground. The theme is further reinforced by the sermon her father gave on Noah’s perseverance in the face of God’s impending destruction. Following the fire that razes Bankole’s land, the group immediately begins to reseed the arable land and rebuild lost houses, embodying the principle that new life can emerge from the ashes of the old.

Parable of the Sower presents a sharp critique of individualism by contrasting the self-interested residents of Lauren’s walled community, Robledo, with the nascent, altruistic society she forges. The walled enclave, a microcosm of societal collapse, is populated by individuals who, driven by self-interest, betray neighbours and neglect children. Their isolationist mindset and rigid adherence to old social constructs prove “untenable” in a world that has fundamentally changed. In stark contrast, the Earthseed community Lauren builds is founded on collective purpose, kindness, and the principle of putting the “group ahead of the individual”. The journey itself, which forces strangers to band together and rely on one another, is the crucible for this new social model.

For writers of social commentary, the lesson of Parable of the Sower is that a compelling dystopia doesn’t require a single, cataclysmic event. Butler’s world is not the result of a nuclear war or a zombie plague but a slow-motion unravelling, disintegrating bit by bit. This societal decay is a direct consequence of the interconnected crises of global warming, growing wealth inequality, and corporate greed. The novel critiques late-stage capitalism and the neo-conservative assault on the welfare state by depicting a world where public services have been privatised, leading to the rise of company towns that recruit people into a form of modern slavery. As the economy collapses, society devolves into lawlessness, with armed gangs, drug addiction, and rampant violence filling the power vacuum.

This portrayal grounds the novel not in fantasy but in a logical, if terrifying, extension of present-day trends. The novel’s recent success is a direct consequence of this frighteningly realistic vision that contemporary readers find all too recognisable. As the world grapples with a deepening climate crisis, political demagoguery, and the rise of populism, Parable of the Sower functions as a warped mirror of where we already are.

The Plain and the Poetic: Butler’s Stylistic Mastery

Octavia Butler’s writing style in Parable of the Sower is a study in contrast, serving as both a narrative device and a reflection of the novel’s core philosophical framework. The narrative is presented as Lauren Olamina’s personal journal, a choice that gives the prose a deceptively simple quality. The writing is plain and straightforward, eschewing ornate language and complex sentence structures in favour of basic “Subject-Verb-Object” construction. Lauren just wants to tell you the truth, and the raw, unadorned nature of her prose makes the harrowing, intense events of the novel feel all the more visceral and authentic. The journal format also blurs the line between fiction and reality, with Lauren noting that reading science fiction helps her to understand her own world, a clever meta-fictional gesture by Butler herself.

This plain prose, however, is juxtaposed with the poetic and philosophical verses of Earthseed, which are distilled into a form that resembles scripture. These verses, presented in short, broken lines, are simple in their content but weighty in their meaning, serving to heighten the seriousness and the emotion of Lauren’s philosophical realisations. This stylistic duality is far from a mere aesthetic choice. It embodies the novel’s central argument: that to survive a profound crisis, one must attend to both the brutal, material realities of the present and the guiding, abstract principles of a new philosophy. The plain prose represents the raw struggle for survival, while the poetic verse provides the higher purpose that makes that struggle meaningful. It suggests that a new society cannot be built on pragmatism alone; it requires a compelling vision to strive towards. By combining these two distinct styles, Butler creates a narrative that is both grounded in reality and soaring in its philosophical ambition, a form that perfectly mirrors the novel’s central argument for a union of practical action and moral purpose.

The enduring impact of Parable of the Sower is a remarkable testament to its foresight. Upon its initial publication in 1993, the novel was critically acclaimed, earning a place on the New York Times Notable Book of the Year list in 1994 and a Nebula Award nomination. However, its success was a slow burn, finding its dedicated audience among science fiction fans, Black readers, and feminists. The novel’s true cultural moment arrived nearly three decades later when it became a New York Times best-seller, transforming the novel from speculative fiction into a chillingly accurate reflection of contemporary reality. The novel has since been adapted into an opera and a graphic novel, while NASA honoured Butler’s influence by naming the Mars rover’s touchdown site “Octavia E. Butler Landing”.

The central insight of the novel is that environmental degradation is not a stand-alone crisis but is inextricably linked to socio-economic and political decline. The book meticulously details how climate change-induced droughts, water scarcity, and extreme weather events lead to a loss of agricultural land, which in turn makes food scarce and people more selfish. This scarcity creates an unpleasant social environment, full of fear and distrust, which exacerbates existing social divisions and leads to lawlessness. The novel’s portrayal of climate migration, with Lauren and her companions forced to travel for survival, is a central part of this and echoes the real-world experiences of millions of people who have been internally or internationally displaced by climate change, particularly those in Central America who are migrating due to droughts.

Unlike many cli-fi novels that are oddly quiet about what initially brought the world to the brink of collapse, Butler’s work explicitly engages with the socio-economic origins of climate catastrophe. This places her in a category with authors like Kim Stanley Robinson, who understand that climate change is a socio-political, not just an environmental, problem.

Perhaps the most controversial and debated element of the novel is the Earthseed philosophy’s ultimate goal: the Destiny of humankind is to take root among the stars. Critics have argued that this vision of space colonisation is a form of escapist libertarian frontierism that undermines the novel’s commitment to solving problems on Earth. This perspective views the Destiny as a selfish, Elon Musk-esque fantasy that is disingenuous to the struggles of marginalised communities and fails to offer a practical solution for the planet’s problems.

However, a more nuanced reading of the novel presents a compelling counterargument. From this perspective, the pursuit of an interstellar destiny is not an act of escape but an evolutionary necessity. It argues that caring for Earth and reaching for the stars are not “mutually exclusive” but “mutually dependent” goals. The grand challenge of colonising another planet could provide the “perspective from outside of Earth” needed to develop the social, technical, and legal systems required to preserve our home planet. In this view, Destiny is a tool and a secular vision for building a more compassionate and inclusive society, free from the conflicts that have plagued humanity on Earth. The ambiguity of this conclusion forces the reader to grapple with a complex question: what kind of grand vision is necessary to motivate a species to overcome its self-destructive tendencies?